Aristotle’s Forgotten Theory of Memory in the Heart

What the Intrinsic Cardiac Nervous System reveals about ancient philosophy, perception, and the nature of recollection.

At The Net session this week, hosted by O.G. Rose, we spoke about memory and attention. Memory is a most curious condition of the soul. To give an example: when I hold in my hands an article of clothing from my father, or when I approach the playground where I used to play as a child, the memories associated with these places and objects feel present-at-hand—independent of my thought or will. What I do with these memories is, of course, within my control and power. Aristotle notes such a dual path of perception when he writes that an object present may not be “brought-before-the-eyes” (ὑποφερομένων ὑπὸ τὰ ὄμματα) if the subject happens to be deep in thought, overwhelmed by fear, or startled by a loud noise (Aristotle, De Sensu 447a). Yet the initial presence of these memory objects is something thrown-before-me. The article of clothing or the playground shows itself as a partial object, both in my hands and in my heart.

I just spoke of the heart of man, and I suspect you took my meaning as a mere figure of speech. Such a figure is not what I intended. Aristotle states that memory is not a faculty but rather a being-acted-upon condition of the soul. Memories, stored as phantasms, are presented to the sensitive soul by a faculty called the common sense. This common sense gathers the five kinds of sensation—taste, smell, sight, hearing, and touch—into a unified phantasm. This same faculty, which perceives time, is also the seat of memory. According to Aristotle, without memory there can be no perception of time (Aristotle, De Memoria et Reminiscentia, 449b).

Now, for Aristotle, the faculties of the sensitive and vegetative soul must have an organ located somewhere in the body. One might expect this organ to be part of the brain. A modern account would suggest the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, or cerebellum as the likely site. But Aristotle thought otherwise. He claimed that the faculty of common sense resides in the heart. For the sensitive soul—which both humans and animals possess—the heart is “the lord of perception” (kyrion tōn aisthēseōn) (Aristotle, De Sensu 469a).

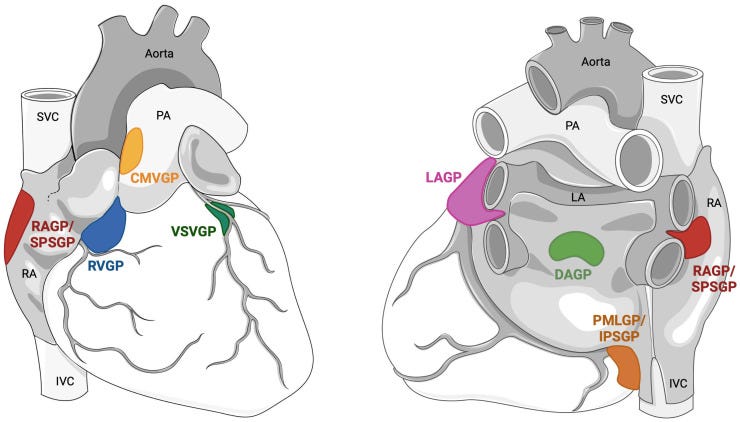

This cardiocentric principle, in contrast to cephalocentrism, was common in antiquity. Such ideas are often cited as evidence that the ancients’ understanding of the body and soul is outdated, since modern “science” offers a more accurate cephalocentric model. I’ll admit, when I reread these passages from Aristotle, I was tempted to agree and to dismiss his biology entirely. But my view changed when I learned about the Intrinsic Cardiac Nervous System (ICNS). Discovered in 1991, the ICNS is a cluster of about 40,000 neurons at the top of the heart that functions independently of the cephalic nervous system. The ICNS exhibits neural plasticity and memory, administering “beat-for-beat” control of cardiac function and response while both receiving and sending signals to higher-order systems in the body (Giannino et al., 2024). Thus, the heart indeed possesses a faculty capable of generating and responding to signals—but how does this connect to memory and recollection?

The common sense gathers the totality of experience into a figure stored like a picture. Aristotle explains recollection as a process of viewing, within the mind, the image of the phantasm unified by the common sense. That picture can be understood as either; a schema; a likeness of reality connected to the phantasm; or as a movement between figures in a mental space. This is possible because a phantasm, originally fixed in the “memory palace,” can later be shifted into relational proximity with another phantasm. Think of word games like Last Word, First Word, where the final word of one sentence becomes the first of the next. If we were to graph these sentences, the linguistic chain would cross a web of potential meanings based on signification proximity. For example:

I went to the store to buy some apples.

Apples are my favorite fruit to eat.

Eat your vegetables if you want to grow up big and strong.

Strong leadership is important for any group.

Group projects can sometimes be challenging.

Returning to the common sense found in the heart: when we experience the dual presence of the memory object and the present object, we begin to see what attention might mean for the human person—and especially for the healthy person. Health is located in the body. For the human being, the virtue of temperance coordinates and orients the body toward good working condition for activities such as phronesis (practical wisdom). Temperance, Aristotle says, safeguards phronesis; without temperance, the soul cannot attend to experience or perceive the patterns revealed through induction. Such induction requires memory to ensoul experience into workable phantasms (Aristotle, Posterior Analytic, II.19).

At a still higher level, for a human to enact the creative power of new revelatory activity—the manifestation of the Beautiful—one must be quick-witted, and thereby excellent in the rapid recollection of resemblances (De Memoria et Reminiscentia, 451a) which “bringing-before-the-eyes” that “A is B.” (Aristotle, Rhetoric, III.11) These agathokalos individuals see with their hearts the deeper realities hidden from ordinary logos. No—rather, this is the analogos that Plato describes in the Phaedrus, where such persons recollect the Beautiful in the place of this particular phenomenon (Plato, Phaedrus, 249d).

Astounding work Thomas, thank you. I will read again. Just this week I was looking into Aristotle's notion of movement and it's origin in perception. The place of the heart in perception suggested here is a real gift to that thinking.